Dear friends

Some of you may have already seen this story that appeared in the leading Indian publication BusinessWorld. Nonetheless, I am taking this opportunity to share this insightful article with you once again, hoping you would take time to read it.

For more details you should refer BusinessWorld's this edition.

This truly is a very special event as for the very first time in the history of IBM, the organization is hosting its investors outside of US and Europe. And the country that gets this honor is India. Also attending this event will be over 43,000 IBM India employees across Bangalore, Pune, Kolkata, Delhi and Mumbai, and getting broadcasted to IBMers worldwide later on. And most importantly the gathering would be addressed by the likes of His Excellency President of India, Dr APJ Abdul Kalam, our Chairman Sam Palmisano, and Sunil Mittal, MD, Bharti Enterprises, among other key dignitaries.

Enough Said.........Here we go ..............

When Sam Palmisano calls, you generally go. Even if it means travelling half way across the globe to a dusty, traffic-clogged, southern Indian city. So, in the first week of June, nearly 50 Wall Street equity analysts will troop into Bangalore to attend IBM Corporation’s annual analysts’ summit.

The summit, generally hosted in New York, has been held in Europe a couple of times. But this is the first time in IBM’s history that the Armonk-based, $91-billion IT giant is asking Wall Street analysts who follow its stock to come so far afield.

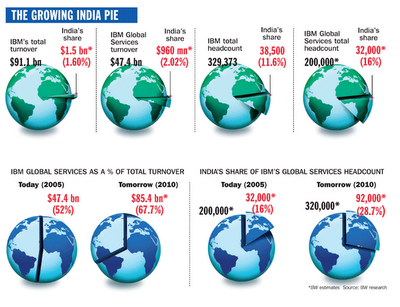

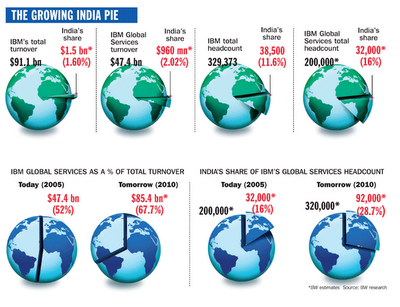

The question that naturally follows is: why Bangalore? At a superficial level, it can be answered by talking about the India growth story. Over the past three years, IBM’s India operations have grown at breakneck speed. IBM India’s headcount at the end of 2005 stood at 38,500 or 11.6 per cent of its total headcount, the most among any centre outside the US. Last year, it recruited 15,500 people in India, even while it shed 14,500 in Europe. IBM services 250 clients across the world from its global delivery centre in Bangalore, which is the only one that can offer solutions across continents. Finally, India revenues have been growing at 60 per cent per year, though from a small base, while IBM’s overall revenues have remained flat.

At a deeper level, though, the answer lies in understanding IBM’s struggle to reinvent itself as a company focused on services solutions. And in understanding why it needs to get its India story right to succeed in that exercise. Palmisano needs to demonstrate to Wall Street analysts that the company is on the right track in its services business. To do that, he has only one real thing to show — the way IBM India has been shaping up. It is India that holds the key to Palmisano’s services gameplan. And that is also why he is looking at a really big ticket acquisition — one of the top five Indian software services companies — to ramp up India operations even further. But that is getting ahead with the tale. First, the reason why India is so important to Palmisano.

Reinventing Big Blue

About four years before Palmisano became Big Blue’s big chief, in January 1998, then IBM top dog Louis V. Gerstner Jr put him in charge of IBM Global Services, which was specifically created in 1991 to offer full computing solutions to clients. When Gerstner had taken charge of IBM, it was a loose confederation of hardware and software businesses working autonomously, and often at cross purposes. He turned it around by knitting it into an integrated computing solutions seller. Palmisano’s job was to rev up growth at Global Services, which had revenues of $19.3 billion (as on December 1997). When he moved to the server business late 1999, it was clocking revenues of $32.2 billion, up 66.8 per cent in 24 months. This success laid the foundation for the top job in 2002.

Today, Global Services accounts for a little over half of IBM’s revenues (the balance comes from hardware, software and global financing). Palmisano’s goal is to take that to 70 per cent in another five years. When Palmisano took over as chief of IBM, two critical pieces were missing from Global Services. First, IBM was absent in high-end consulting services. Two, it lacked a low cost base for executing services work. IBM was strong in traditional areas of computer maintenance and support, but margins were getting increasingly squeezed in those areas. More importantly, these were legacy contracts and new clients were looking for something very different — service providers who help them transform their businesses and also take up the responsibility for managing many of their functions.

Nine months after taking over, Palmisano pushed through the acquisition of PricewaterhouseCoopers’ consulting arm. This removed one weakness. With 30,000 PwC consultants on board, Palmisano could bid as aggressively for consulting projects as an Accenture could. (As part of its overall strategy, IBM also shed its commodity PC business by selling it to Chinese PC maker Lenovo in early 2005.)

The big India push of the past three years — which includes the takeover of the BPO company Daksh eServices for $160 million and ramping up its delivery centres in Bangalore — is meant to remove the second weakness. A small point here — the India strategy is part of IBM’s overall plan to create four delivery hubs in the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China) countries to bring down cost of operations. However, as we will see, India is way, way ahead of the other three.

The BRIC plan has been clearly laid out. Essentially, over the long term, it will use these four hubs to offer clients the best deals at extremely competitive prices. Brazil, where it has over 6,000 people, is expected to become its offshore hub for tapping the Latin American market, as well as a nearshore option for US customers. Russia, a nascent operation, gives IBM a nearshore but low-cost solution for the diverse European market. Its big advantage in Russia is a large per capita pool of engineers — 3,500 for every 1 million people. Then there’s China. Compared to India, IBM has just 7,000 people in China doing offshore, but the country has a huge domestic market over which IBM has established a stronghold over a 15-year period. India, as Micahel Cannon-Brookes, vice-president (business development, China and India), puts it and as IBM sees it, is at the epicentre of the flat world. In 2005, the BRIC countries collectively ploughed in $3.8 billion in revenues and employed close to 60,000 people.

Among these four, India has not only gained critical size but is also growing the fastest. Besides, with 38,500 employees, India is a bigger operation than the other three put together.

Palmisano’s strategy is based on the premise that IBM’s consultants in the US should be able to sell high-end, high-margin consulting solutions to clients across the globe and then have those solutions implemented out of its base in India. It is not something that others haven’t thought of — practically every one of its rivals is following the same strategy, including Accenture and EDS. And Indian software services companies like TCS, Wipro and Infosys are trying to transform themselves into end-to-end solution providers by adding consulting services to their traditional range of offerings.

The weapon IBM hopes to use to bludgeon its rivals is the sheer size and depth of its offerings. Consider this — at $47 billion, the Global Services business dwarfs the next competitor, the $19.8-billion EDS. Moreover, no one can offer the kind of integrated solutions IBM can, such as consulting, maintenance, BPO and remote infrastructure solutions. It can offer solutions practically in any industry and in any part of the world. It can also offer R&D solutions — it spends an average of $5 billion on R&D every year. No one player among its rivals has the breadth of offerings that it has.

The problem: because of legacy costs, IBM can’t provide those services particularly cheaply.

The question is, can IBM ramp up its low-cost operations in India while winding down its high-cost operations across the globe fast enough?

Even till 2001, IBM India was a sluggish and unimaginative IT company. Over nine years of operations, revenues had just about crossed $300 million and staff strength was around 4,000. IBM’s bid to redefine itself globally as a services player had not made any material difference to its India operations. Then, two things happened within a span of 12 months. In January 2001, Abraham Thomas took charge as CEO and managing director of IBM India, after having spent a significant part of his 14-year career at IBM in senior positions in the Asia-Pacific region. But more importantly, Palmisano became chairman of IBM in March 2002. With Palmisano and Abraham at the helm of affairs in Armonk and Bangalore respectively, IBM India went on a growth overdrive and the chairman became an annual visitor to Bangalore. India revenues jumped from $350 milion in 2002 to $937 million in 2004, the year Abraham moved back to Singapore. His successor, Shankar Annaswamy, has kept the momentum on track and in 2005, IBM India crossed the $1-billion revenue mark.

Two events particularly signalled IBM’s new growth drive in India. First, in March 2004, IBM’s India team clinched a $750-million IT outsourcing contract from Bharti Tele-Ventures, beating rival bids from HP and Oracle. A month later, it acquired Gurgaon-based call centre Daksh eServices. The Bharti deal gave IBM India the much-needed inroad into the domestic Indian market, and Daksh catapulted it among the top five BPO service providers from India. All these were part of Palmisano’s overall game plan to leverage India and ramp up its presence in the country really fast.

Under Palmisano, IBM bet on three key trends taking off — Linux, on-demand computing and, finally, emerging markets not just as a low-cost base, but also as a market (all part of the Global Services portfolio). India figured heavily on all three counts. In 2001-2002, a part of the $1 billion that IBM spent on promoting Linux went into setting up the Linux Center of Competency in India. Subsequently, a large chunk of its $1-billion research budget for e-business came to the India Research Lab. But the primary focus was on global delivery. The explosive growth it has seen in global delivery out of India is what has driven IBM’s growth here.

Since 2004, Palmisano has accelerated the India initiatives. He has reorganised the India team to drive growth in line with IBM’s global objectives. Most of the senior India management team, for instance, does not report directly to Annaswamy. So, former PwC Consulting man Amitabh Ray, head of IBM Global Services India, reports directly to IBM Global Services’ chief Ginni Rometty. “This helps get rid of the bureaucracy and makes decision-making faster,” says a company source. Inderpreet Thukral, director (strategy and business development), has been deputed to drive growth in emerging business opportunities in India. That focus was further emphasised in 2005 when Palmisano deputed Shanghai-based Michael Cannon-Brookes, an old IBM hand in Asia, to take special charge of China and India. Cannon-Brookes’ mandate is to oversee strategy for both these markets and align them with IBM’s globally integrated services game plan. Thukral reports to Brookes, who sees his job as one that facilitates a sharper focus withi n the IBM leadership in India. He says: “You go not only where the growth is, but also where the new pools of talent are — obviously India and China. It was necessary to take a more longer term view beyond day-to-day operations. So, we had to get a focus within the company at the senior level on these two markets.”

So, as the India organisation structure stands today, Annaswamy, apart from being managing director for IBM India, also oversees growth in the domestic market. The focus is important because the market for IT outsourcing services in India is just beginning to open up. In fact, according to sources, the domestic business is likely to be spun off into a strategic business unit and expansion plans this year include 40 additional tier-II cities. “There are plans to set up dedicated delivery centres for the domestic market,” say sources. Cannon-Brookes and Thukral take care of the longer-term strategic imperatives. The jewel in the crown, global delivery services, includes within it IBM-Daksh and what IBM calls the business transformation outsourcing (BTO) practice, remote infrastructure management and application development and maintainence. The decentralised structure enables each unit to function independently and, thus, grow faster. The 32,000 people global services operation in India is almost evenly split between BPO services offered by Daksh (18,000 people) and other offerings (14,000 people).Of late, IBM has been using the global delivery services in India to win contracts. In fact, the newly acquired global delivery capability in India helped it clinch the recent $2.2-billion ABN Amro deal. A large chunk of the new application development work for ABN Amro will be executed by IBM out of India. According to Ray, the year-on-year growth on the global delivery front has only started taking off. “In two years, we will be the biggest IT services company in India,” he says.

There have been other more subtle, but equally important, changes in India. Thukral and Ray are good examples of the change — they straddle both India and global roles, while being based in India. “That’s a huge cultural shift for IBM,” say sources. It is as much about India’s growing significance in the IBM frame of things as it is about IBM’s bid to shed its former identity of a US-centric, bureaucracy-driven heavyweight.

So, as the India organisation structure stands today, Annaswamy, apart from being managing director for IBM India, also oversees growth in the domestic market. The focus is important because the market for IT outsourcing services in India is just beginning to open up. In fact, according to sources, the domestic business is likely to be spun off into a strategic business unit and expansion plans this year include 40 additional tier-II cities. “There are plans to set up dedicated delivery centres for the domestic market,” say sources. Cannon-Brookes and Thukral take care of the longer-term strategic imperatives. The jewel in the crown, global delivery services, includes within it IBM-Daksh and what IBM calls the business transformation outsourcing (BTO) practice, remote infrastructure management and application development and maintainence. The decentralised structure enables each unit to function independently and, thus, grow faster. The 32,000 people global services operation in India is almost evenly split between BPO services offered by Daksh (18,000 people) and other offerings (14,000 people).Of late, IBM has been using the global delivery services in India to win contracts. In fact, the newly acquired global delivery capability in India helped it clinch the recent $2.2-billion ABN Amro deal. A large chunk of the new application development work for ABN Amro will be executed by IBM out of India. According to Ray, the year-on-year growth on the global delivery front has only started taking off. “In two years, we will be the biggest IT services company in India,” he says.

There have been other more subtle, but equally important, changes in India. Thukral and Ray are good examples of the change — they straddle both India and global roles, while being based in India. “That’s a huge cultural shift for IBM,” say sources. It is as much about India’s growing significance in the IBM frame of things as it is about IBM’s bid to shed its former identity of a US-centric, bureaucracy-driven heavyweight.

But Questions Remain

India is growing explosively, but is it growing fast enough to make a difference to IBM? That is the question analysts are beginning to ask. The questions are valid because, of late, IBM Global Services seems to be struggling. A year ago, it missed both its revenue and earnings targets. High-cost operations in Europe and sluggish European markets were identified as the root cause of that miss.

That miss was the primary reason why IBM decided to shed 14,500 jobs from its European operations — 14.5 per cent of 100,000 it had there. That caused huge protests and much pain within IBM, which had always tried to project itself as a company that offered jobs for life. One big loss was the exit of IBM Global Services’ chief John R. Joyce, who quit in July 2005. Joyce left two months after the job cuts in Europe were announced. But, so far, Palmisano hasn’t let the pain deter him.

In the latest quarter again, IBM Global Services’ revenues have been flat. The trend continues from last year. Revenues grew 2.1 per cent in 2005. Gross profit margins were also unimpressive: 25.9 per cent in 2005 against 25.1 per cent in 2004.

Clearly, Global Services seems to have hit some sort of a plateau. The PwC acquisition is not yet bringing in the kind of heavyweight business IBM had hoped for. More importantly, with topline of the global services business largely flat, IBM needs to make sure that at least the bottomline is improving. And for that, it needs to cut jobs drastically in the US itself, which is likely to be far harder to accomplish than Europe. By some estimates, IBM needs to slash its US employee strength of 260,000 by half. Before it can do that, IBM India will have to be able to take up the workload of those 130,000 people that it needs to shed — and that is going to be the key factor.

A couple of influential IBM watchers feel that for India to make a significant difference to IBM’s bottomline and topline, Big Blue needs to make at least one more spectacular acquisition, perhaps of one of the top five Indian services firms. Enough organic growth simply cannot happen in the timeframe IBM needs to put the global services business on track. Sometime back there were rumours that IBM was shopping for Satyam, but Satyam chief B. Ramalinga Raju had scotched those rumours. There’s talk in the market currently that IBM is looking closely at a north Indian software services firm, though the company refuses to talk on the subject.

Can Palmisano handle all those problems? He has the will and IBM has enough cash to take hard decisions. What remains to be seen is how the cards fall for IBM in India now.